(Originally posted December 8, 2010)

I often start to write these blogs in my head, which saves time when I can edit in there as well. Last week in NYC, walking blissfully through a Central Park ablaze with glorious fall color, I was playing with the idea of using Oz as a metaphor for the role the city has played in my life. At the exact instant I thought naw, yellow brick roads of possibility is going to sound trite, a tumultuous windstorm came out of nowhere, lifting thousands of leaves high into the air. Runners halted, mothers covered their children’s heads, tourists like Geoff and I, stunned, looked around dumbly, as if for the culprit. It was a truly serendipitous moment, magical, but also a bit unnerving. Classic New York.

I was in New York ostensibly to help my second son relocate from London. Secretly however, I also went in hopes a week there would shake me from the awful mood I had been unable to vanquish since the election. The tenor of discourse in the country has fallen so low, grown so ugly, I have begun to fear that nothing good will ever come from the way we currently practice democracy. Where are we going as a nation? Who are we anymore? As the world sinks into what feels like unprecedented violence, both natural and man-made, too many Americans have resorted to a mindset ever more petty and short sighted, deeply mistrustful of anything which requires intellect or reason.

In the past New York has afforded me solace, if not answers to questions like these. I was 16 when my despairing parents, “at our wits end!” shipped me off to a very rich aunt who lived on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. They were expecting a miracle, or, failing that, a short course finishing school. My aunt took one look at me in full hippie attire, a backpack of contraband and a guitar I could not play slung over my shoulder, threw up her hands and promptly decamped to her daughter's house in Connecticut. The closest thing I had to minders for the rest of the summer was a cabal of doormen who thought I was crazy. I wasn’t. I was confused and deeply disillusioned, mostly about the war in Vietnam.

Though I only lasted the summer, by happenstance several things conspired to keep me safe and propel me to a place where I began the long journey trying to make sense of Power with a capital P, and the creaky way it turns most people’s lives on history’s spit. I was young, dumb and stoned enough most of the time not to fear the city, and as I was intrepid in my appetite for adventure, explored Manhattan from Harlem to what was then a meatpacking district with actual butchers. Coming from monosyllabic LA, where vocabulary basically consisted of only three statements ~ “far out,” “that’s cool (especially when something wasn’t), and “bitchen” (when something was), I was fascinated with the way new yawkers talked, talked, talked. Everyone, from the countess across the hall to the taxi drivers who picked me up late at night, dispensed advice. In Paris success in social conversation resides in the perfect bon mot, in Italy the well chosen hand gesture, in New York it means 'having the last word.' Which of course is not a word at all, but a stream of passionate, opinionated, often colorful lectures that fall somewhere between a short story and a graduate thesis. On any subject. Even if marginally not worth talking about in the first place.

On long hot muggy days, waiting for night to fall, I stalked the halls of great old American buildings stuffed with Robber Baron art, starting with the Frick, one of greatest small museums in the world, which happened to be right across the street. It was my first exposure to art where I wasn’t tagging along with my mother, or forced to look at muddy prints in boring school lessons. Experiencing it on my own, from a vulnerable yet curiously open place, it opened my eyes to a number of things. The first was that Americans didn’t understand sex or the female body, (I was from LA, remember, which still doesn’t). It was incredibly exciting to know there was a whole sensual world out there. The second, which spoke directly to the pain I was in, was the extent to which art was a valuable witness to the misuse of power that is repeated in every age, no matter who the man was behind the curtain is. What was taking place in my lifetime wasn’t an aberration of history. While I must have already known this on some level, instead of making me even sadder, as I studied canvas after canvas of masterful paintings and sculpture going back more than 500 years, I began to see a concurrent theme of hope and ambition. One that, against the odds, almost seemed to be fueled by adversity. The history of art is the history of an indomitable human spirit, a hunger not just to survive, but to see the beauty in life, bruised though it may be. Life is opportunity, which for an artist starts with the very impulse to pick up a brush or chisel.

On long hot muggy days, waiting for night to fall, I stalked the halls of great old American buildings stuffed with Robber Baron art, starting with the Frick, one of greatest small museums in the world, which happened to be right across the street. It was my first exposure to art where I wasn’t tagging along with my mother, or forced to look at muddy prints in boring school lessons. Experiencing it on my own, from a vulnerable yet curiously open place, it opened my eyes to a number of things. The first was that Americans didn’t understand sex or the female body, (I was from LA, remember, which still doesn’t). It was incredibly exciting to know there was a whole sensual world out there. The second, which spoke directly to the pain I was in, was the extent to which art was a valuable witness to the misuse of power that is repeated in every age, no matter who the man was behind the curtain is. What was taking place in my lifetime wasn’t an aberration of history. While I must have already known this on some level, instead of making me even sadder, as I studied canvas after canvas of masterful paintings and sculpture going back more than 500 years, I began to see a concurrent theme of hope and ambition. One that, against the odds, almost seemed to be fueled by adversity. The history of art is the history of an indomitable human spirit, a hunger not just to survive, but to see the beauty in life, bruised though it may be. Life is opportunity, which for an artist starts with the very impulse to pick up a brush or chisel.

We stayed at The Surry for the first three days, a hotel not far from my old haunting grounds. In the clear bracing sunshine we walked in the park, took our time over delicious prix fixe lunches at Café Boulud (which happily was attached to our hotel), then climbed the big steps of the Met and went our separate ways, or slowly trailed each other, until just before closing. Below are my notes on a few of the shows that I saw. The Barndiva Newsletter is primarily focused on food and art; both are sources of nourishment without which we cannot survive. But even if you are not traveling East in the next few months, the diversity of what you find in any great museum is essential viewing. The Met, sadly, is one of the few in NY that is still free if you do not have the money to donate ‘an appropriate’ entrance fee. It astounds me that we are making fine art an elitist sport in this country when it offers one of the few singular opportunities for citizens of all persuasions (income levels, ethnicities, religions) to come together in consideration of shared human values. Go to a museum and look around, not just at what is on the walls.

I won’t lie: while my time in NYC’s museums and parks topped up a flagging spirit, the most important moments for me on this trip were those I spent with my family. Seeing the Metropolitan Opera’s Così fan Tutte with my daughter ~ her first opera experience. Having a grown son know enough about New York (and for that matter, life) to guide us straight into Bemelmans Bar when the sky opened and a sudden rainstorm clamored down. Noisy and late dinners at Del Posto, abc kitchen, Pastis, where, for a few hours, it was permissible to believe that good restaurants, the ones that source with their hearts and take care to provide great service, like Barndiva, will survive this recession. (A glass raised to Mario Batali who has the biggest balls right now in this big balled restaurant town, not only for what it took to build the beautifully retro Del Posto and take it to four stars, but for his just launched and truly audacious attempt, with his partners, the mother and son Bastianich, to create America’s first great food hall in Eataly).

I won’t lie: while my time in NYC’s museums and parks topped up a flagging spirit, the most important moments for me on this trip were those I spent with my family. Seeing the Metropolitan Opera’s Così fan Tutte with my daughter ~ her first opera experience. Having a grown son know enough about New York (and for that matter, life) to guide us straight into Bemelmans Bar when the sky opened and a sudden rainstorm clamored down. Noisy and late dinners at Del Posto, abc kitchen, Pastis, where, for a few hours, it was permissible to believe that good restaurants, the ones that source with their hearts and take care to provide great service, like Barndiva, will survive this recession. (A glass raised to Mario Batali who has the biggest balls right now in this big balled restaurant town, not only for what it took to build the beautifully retro Del Posto and take it to four stars, but for his just launched and truly audacious attempt, with his partners, the mother and son Bastianich, to create America’s first great food hall in Eataly).

I also won’t lie that all those experiences cost money. A not inconsiderable amount of it. My point is that even as we feed the essential personal narratives in our lives, to whatever extent we find important and can afford, we need to make time to consider upping our participation in institutions and public open spaces that everyone can enjoy and reflect in.

On one of our last days Geoff and I walked the new High Line Park, on the lower east side, where we were now staying. Even in the cold, without the families with dogs and young children, it was easy to see what a wonderful addition this park is to the city. Designed by the always excellent Diller, Scofidio + Renfro out of a raised rail track built in the 1930’s but unused for the past thirty years, it instantly transforms one’s view of the city ~ not just the views down into the streets, but an inner view of what it means to reclaim and interact with awkward unused urban spaces. The High Line is a sculptural park with simple but sinuous benches of concrete and old wood that rise up out of the old tracks. The hardscape is softened with a landscaping plan by James Corner primarily of grasses which pay homage to what had been growing there wild, since the trains stopped running.

I was greatly impressed with Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart's Renaissance, an exhibit of lush representational color with a politically subversive subtext which must have raised eyebrows at the time. The Dutch empire fell from a height of considerable power for sins of hubris, so make your own connections on that score. This was a good one for me to see right now.

I was greatly impressed with Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart's Renaissance, an exhibit of lush representational color with a politically subversive subtext which must have raised eyebrows at the time. The Dutch empire fell from a height of considerable power for sins of hubris, so make your own connections on that score. This was a good one for me to see right now.

In conjunction with viewing the work of Gossart, I was really looking forward to an exhibit of a series of Joan Miró pieces that the great Spanish artist did shortly after he returned from studying the Dutch masters at the start of his career. But while the works in Miró: The Dutch Interiors makes clear the colorful and compositional connections between what would seem two remarkably incompatible styles, the show was not as revealing as I hoped. Not really a surprise: Miró is to the Dutch movement like Jeff Koons is to real sex. Having said that, for me, a day where you can see three roomfuls of Mirós, even marginal ones, is always a joy.

In conjunction with viewing the work of Gossart, I was really looking forward to an exhibit of a series of Joan Miró pieces that the great Spanish artist did shortly after he returned from studying the Dutch masters at the start of his career. But while the works in Miró: The Dutch Interiors makes clear the colorful and compositional connections between what would seem two remarkably incompatible styles, the show was not as revealing as I hoped. Not really a surprise: Miró is to the Dutch movement like Jeff Koons is to real sex. Having said that, for me, a day where you can see three roomfuls of Mirós, even marginal ones, is always a joy.

Of the exhibits I managed to see, I was least impressed with John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, the much touted show of the season, which, intended irony aside, simply was not. (beautiful) For me this show was another case of the Emperor's New Clothes a la Art Basel. From all accounts Baldessari was a great teacher, but in even his strongest work here (and with the exception of what he burned in the 70’s, it's all here) this is art with a heart of stone, wordplay that is dated, video that makes me long for Nam June Paik. Baldessari is an LA artist in the same way Frank Gehry is an LA architect. There is great irreverence here to be admired, a “take that” attempt at disarming pretension anyone hoping to survive LA must have in their DNA, but whereas Gehry plays to his strengths in three dimensions, Baldessari’s antipathy to negative space produces work that is flat and ugly, devoid of even a rueful use of color. I would love someone to explain why this shit works for them.

Of the exhibits I managed to see, I was least impressed with John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, the much touted show of the season, which, intended irony aside, simply was not. (beautiful) For me this show was another case of the Emperor's New Clothes a la Art Basel. From all accounts Baldessari was a great teacher, but in even his strongest work here (and with the exception of what he burned in the 70’s, it's all here) this is art with a heart of stone, wordplay that is dated, video that makes me long for Nam June Paik. Baldessari is an LA artist in the same way Frank Gehry is an LA architect. There is great irreverence here to be admired, a “take that” attempt at disarming pretension anyone hoping to survive LA must have in their DNA, but whereas Gehry plays to his strengths in three dimensions, Baldessari’s antipathy to negative space produces work that is flat and ugly, devoid of even a rueful use of color. I would love someone to explain why this shit works for them.

Which is not to say that living the vida loca (modern life IS crazy) does not come with a concomitant desire to take a deeper look at why post war prosperity ultimately led to the American soul becoming disenfranchised. American’s suffer from a misconception of what material wealth really brings to the table, that much is clear and sorely needs to be addressed. Lee Friedlander: America By Car at the Whitney (which I wandered into by accident on my way to visit the Hopper exhibit upstairs) is the real deal. Taken over the last decade through his car window while he crisscrossed America, it is one of those shows that builds as you move through it. The exhibit is a revelation that speaks to Friedlander’s talent for composition which brilliantly straddles wit with profundity. Image after image reveals what happens when our insatiable hunger for illusion gets left by the roadside. Like unfinished poems, the detritus and people he captures along the highways and byways of this country made the point about junk culture the Baldessari exhibit didn’t. Think Wim Wenders of Paris, Texas crossed with Bruegel the Elder if you transferred his work to black and white and then set to having some fun with a mimeo machine.

Which is not to say that living the vida loca (modern life IS crazy) does not come with a concomitant desire to take a deeper look at why post war prosperity ultimately led to the American soul becoming disenfranchised. American’s suffer from a misconception of what material wealth really brings to the table, that much is clear and sorely needs to be addressed. Lee Friedlander: America By Car at the Whitney (which I wandered into by accident on my way to visit the Hopper exhibit upstairs) is the real deal. Taken over the last decade through his car window while he crisscrossed America, it is one of those shows that builds as you move through it. The exhibit is a revelation that speaks to Friedlander’s talent for composition which brilliantly straddles wit with profundity. Image after image reveals what happens when our insatiable hunger for illusion gets left by the roadside. Like unfinished poems, the detritus and people he captures along the highways and byways of this country made the point about junk culture the Baldessari exhibit didn’t. Think Wim Wenders of Paris, Texas crossed with Bruegel the Elder if you transferred his work to black and white and then set to having some fun with a mimeo machine.

My favorite show this fall, perhaps because I was on a lover's journey in New York, was Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand which takes up a number of connecting backrooms at the Met. Stieglitz, the master teacher, and his two most famous protégées (who arguably overtook him in the craft) captured images from a mindset we hardly remember now as the instant documentary aspects of the medium have subsumed the painterly qualities they sought to capture. In addition to being beautiful in their own right, most of these images are fragrant love letters to New York, and while I have seen many of them before, seeing them collected together in room after room, made me realize that all the bells and whistles we've added to the medium of photography hasn't done as much to capture its soul as envisioned by these pioneers. Technical virtuosos in their day, while that aspect of their work is no longer remarkable to our 21st Century eyes, their approach to the details of everyday life is all the more thrilling when you realize so much of what they captured happened in the incredible city right outside the door of the museum.

My favorite show this fall, perhaps because I was on a lover's journey in New York, was Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand which takes up a number of connecting backrooms at the Met. Stieglitz, the master teacher, and his two most famous protégées (who arguably overtook him in the craft) captured images from a mindset we hardly remember now as the instant documentary aspects of the medium have subsumed the painterly qualities they sought to capture. In addition to being beautiful in their own right, most of these images are fragrant love letters to New York, and while I have seen many of them before, seeing them collected together in room after room, made me realize that all the bells and whistles we've added to the medium of photography hasn't done as much to capture its soul as envisioned by these pioneers. Technical virtuosos in their day, while that aspect of their work is no longer remarkable to our 21st Century eyes, their approach to the details of everyday life is all the more thrilling when you realize so much of what they captured happened in the incredible city right outside the door of the museum.

Links: The High Line The Surrey Hotel (I booked The Surrey at half price on Jetsetter which you can join for free.) My favorite travel site, Tablet, also has auctions every week worth checking out if you are willing to spend a bit more on boutique accommodations. SoHo House- These are among the biggest and most comfortable rooms in Manhattan if you can take the neighborhood which parties on Fridays and Saturdays until the wee hours. Great spa and you are graciously invited to all the in-house events. I came back from dinner too late one night for the premier of Paul Haggis' The Next Three Days but I crashed the after party and though I knew not a soul, had a good time.

(originally posted November 17, 2010)

Ever wondered what it looks like above Barndiva? Here's your chance. Great images and recipes by Chef Ryan accompany the article by Sarah Lynch in California Home + Design Magazine.

Raising the Barn: An International Aesthetic Meets the Best of Wine Country's Heartland

Photography by Drew Kelly and Brad Gillette

LEFT: Studio Barndiva’s eclectic offerings include local artwork and imported accessories, but the blue fireplace—adorned with a Magritte-worthy “It is not a fireplace”—makes it clear that visitors can always expect a surprise. TOP RIGHT: Jil and Geoffrey Hales built their barn (right) from scratch.

The perfect evening out brings together three elements: a delicious meal, a warm atmosphere and lively conversation. For Jil Hales, the proprietor of Healdsburg’s Barndiva restaurant, the bar is set significantly higher because the bar is where it all began.

“We came to Healdsburg eight years ago, after raising our kids in the U.K. and living in San Francisco for a few years,” says Hales, a Los Angeles native married to Geoffrey, a Brit, who brought his hardwood flooring company to the U.S. “What this town was missing was a world-class bar—a place to get a cocktail and a bite to eat late at night.”

LEFT: The kitchen island in the pied-à-terre was fitted with fluorescent lighting and colored gels as a prototype for the restaurant bar. RIGHT: A farm-worthy monitor, painted salmon pink, in the center of the ceiling will one day be accessed by a catwalk.

While the Hales were dividing their time between London and a fruit farm in Anderson Valley that Jil has owned for 30 years, they bought a property just off the town square in Healdsburg and built a two-story barn from the ground up. Downstairs, the bar and restaurant serve the best cocktails in town and an ever-evolving menu of farm-to-table dishes. Upstairs is the Hales’ pied-à-terre. Acting as general contractor and chief designer of the barn was an all-encompassing project, and Jil lived up to the nickname her friends had given her when she first moved to Anderson Valley: the Barn Diva.

Adapting the name to her new venture, Jil’s restaurant suitably hits a few high notes. From the outside, the building suggests a familiar rural vernacular—it’s a single structure with richly stained board-and-batten siding. Inside, the towering space is a sophisticated mix of travertine floors, wood tables, a colorfully lit bar and cream-colored walls adorned with modern art and antique farming tools. Out back, an enclosed garden is set with tables, big rustic sculptures and a trickling water feature; overhead mulberry trees are draped with twinkling fairy lights and a heritage black walnut offers dappled shade during the day.

FROM LEFT: The Cor-Ten steel and neon lights in Barndiva’s sign hint at the owners’ modern sensibilities; Studio Barndiva represents local artists such as painter Laura Parker and wire sculptor Ismael Sanchez; floor-to-ceiling drapes, formal flower arrangements and streamlined drum shades are just some of the sophisticated designs Jil chose for the restaurant; before coming to Barndiva

The pied-à-terre upstairs, which is accessed through the front door tucked alongside the restaurant’s entry patio and up a Dan Flavin-esque staircase with rainbow fluorescent risers, is even more of a surprise. It feels like a loft in Tribeca rather than a barn apartment in Sonoma County. The voluminous main room is centered on an oval dining table surrounded by red leather Eames Executive chairs. On one side a 16-foot-long kitchen island is topped with another fluorescent-lit bar (the prototype for the bar downstairs). The kitchen itself is an updated take on the European unfitted kitchen, with open storage, several sinks and a formidable black-enamel Lacanche range. A built-in bar adorned with Jil’s favored Tunisian ironwork, more classic midcentury furniture and artwork collected from around the world complete the scene in the main space. On one end is a guest bedroom and office mezzanine, and on the other is a master suite.

Two-and-a-half years after completing the barn, the restaurant was bustling on evenings and weekends, and Jil was ready to raise the bar even higher. The Hales’ life in Healdsburg had become increasingly focused on the community around them as they supported local vintners and farmers. But Jil’s passion for art and design needed an outlet, and the four walls of the restaurant were filled. So in 2007 she opened a gallery next door in a space that was formerly an opera house. Artists & Farmers, as it was originally called (now Studio Barndiva), was a place to celebrate and sell the art and designs she discovered locally or on her many travels. On display is an assemblage of Hales’ own lighting made from Tunisian architectural salvage along with locally crafted paintings, wire sculptures, blown glass, reclaimed wood furniture, imported gifts and accessories. “I don’t want to show things that can be easily found somewhere else,” says Hales, pointing out one exception: aselection of John Derian back-painted glass plates. “I know he’s in lots of other shops, but he’s a friend.”

LEFT TO RIGHT: The restaurant’s back patio features pendants that Jil fashioned from Tunisian window guards; fluorescent lights show up at the bar, where a circular backlit inset mimics the two round windows at the top of the building; the entrance to the private residence is marked by a dramatic glowing staircase; the weather in Healdsburg makes it ideal for outdoor wedding receptions.

Behind the gallery is yet another garden. This one is filled with raised vegetable beds, outdoor sculpture and a table large enough to seat 200 under an armature designed for a canopy of mini-globe lights. Like the garden on the other side of the fence, the setup begs for a modern country wedding and it’s been a popular spot for such events since it opened. In fact, Geoffrey and the couple’s eldest son, Lukka, run Barndiva’s event and hospitality business, and they’re now averaging 60 weddings a year. The Hales have also taken over management of the nearby Healdsburg Modern Cottages, four nightly cottages authentically furnished with pieces by Eileen Gray, George Nelson, and Ray and Charles Eames.

LEFT: The humble facade of Barndiva belies the stylish elegance of the experience inside. RIGHT: An outdoor area behind the gallery is attached to the restaurant’s garden through a gate and is a popular spot for wedding receptions.

In her mission to open a world-class bar in this sleepy town, Jil has elevated the creation of the perfect evening to an art form. “I went for the type of environment where I would want to share a meal or toast a special occasion with friends,” she says. “If something doesn’t come from the heart, it just doesn’t work. If you’re not authentic, you’re running on fumes.”

Sitting under twinkling lights, as a parade of seasonal dishes made by Thomas Keller–trained chef Ryan Fancher, original cocktails and wine selected by the in-house sommelier passes by, it would be hard to argue against that.

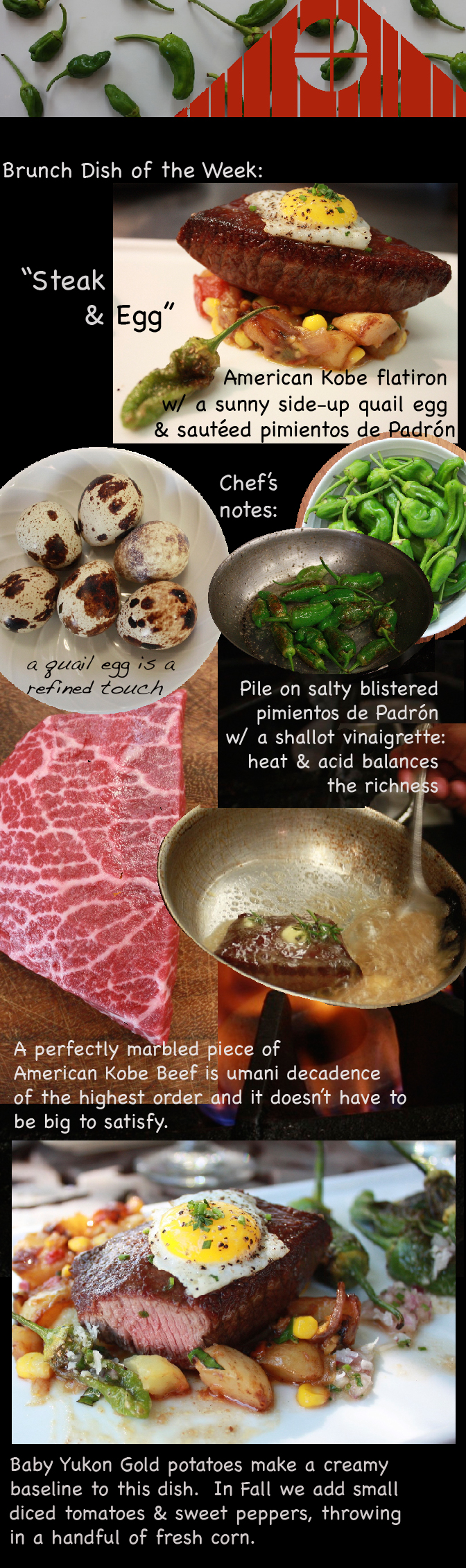

Recipes from Barndiva’s Chef Ryan Fancher

Both of these recipes make the most of fruit and vegetables in late summer or early autumn, when ingredients are at the height of their season. They are great dishes to source at a local farmers market.

Barndiva’s Heirloom Tomato & Compressed Watermelon Salad Serves 4

1 medium watermelon 1 tsp. lemon verbena 1 large golden beet 1 large Detroit dark-red beet 6 heirloom tomatoes 2 Tbsp. sweet basil 4 Tbsp. Spanish sherry vinaigrette Salt and freshly ground pepper 1 cup purslane (optional) 2 Tbsp. crystallized ginger, diced 2 red radishes

Spanish Sherry Vinaigrette 1 cup grape seed oil 1/3 cup Spanish sherry vinegar A pinch of salt, sugar and freshly ground pepper

• The Watermelon - The night before or a few hours before serving, cut into large cubes and sprinkle with the chopped lemon verbena. Wrap tightly in plastic wrap and refrigerate. • The Beets - Cover with 2 cups water, 1 Tbsp. butter, 1 clove garlic and a sprig of thyme. Cover and cook at 350° for 3 hours. Cool and slice. • The Heirloom Tomatoes - Slice them thickly and mix them in with the chopped sweet basil. In a bowl, whisk together all of the ingredients for the vinaigrette. Bathe the tomatoes in 4 tablespoons of the vinaigrette for 30 minutes or more. Season with salt and freshly ground pepper. • Assemble - Stack the tomatoes, largest one on the bottom. Arrange the watermelon. Dress the beets in the bathing vinaigrette, season with salt and pepper, and plate. Sprinkle ginger and thinly sliced radishes over the dish. Dress the purslane, and add it to the dish to finish.

Herb-Roasted Local Halibut Serves 4

8 baby artichokes 2 Tbsp. canola oil 4 cloves garlic 2 springs rosemary Salt and pepper 20 fava beans 1 zucchini 1 gold bar squash 5 lbs. Roma tomatoes 15 Toy Box cherry tomatoes 2 Tbsp. extra virgin olive oil 4 6-oz. halibut filets 1 Tbsp. butter 1 cup tempura batter 4 squash blossoms

Tempura batter 1/2 cup flour Corn starch 1 tsp. baking powder 1/2 cup sparkling water Salt

• The Baby Artichokes - Peel the outside layers to reveal the heart. In a hot pan, roast the artichokes with canola oil, garlic and rosemary until soft. Season with salt and pepper. • The Fava Beans - Peel the favas, and cook them in boiling salted water for one minute. Let cool. • The Summer Squash - Cut the zucchini and squash into diamond shapes, and cook them just like the fava beans. • Vierge sauce - Puree the tomatoes, and strain the clear liquid from the tomatoes through a clean kitchen towel. In a saucepan over medium heat, reduce the liquid by half, and season with salt and pepper. Drizzle extra virgin olive oil. • Halibut - In a hot sauté pan, sear the fish until golden brown, being careful to not overcook. Baste with butter, garlic and rosemary. • Assemble - Pool the sauce in a bowl or shallow plate. Arrange the vegetables in the sauce, and nestle the halibut in the middle. In a bowl, mix the tempura batter’s ingredients, and dress the blossom lightly with the tempura batter. Fry in 350° oil until golden, and place on top of fish.

(originally posted October 13, 2010)

-

The compulsion to make art has been with us for 17,000 years. For most of that time, the foremost question asked of the artist (perhaps second only to where’s the rent) has been why do you do it ~ where does this unstoppable urge to create come from? It’s a fascinating question especially if you’ve never had the calling, but beware the loquacious artist ~ Picasso pops to mind ~ who can come up with what sounds like a dazzling answer to what is ultimately a goose chasing question.

“You might as well ask me why I get out of bed in the morning,” an artist friend once explained, to this day the most refreshingly honest answer I’ve heard. By and large, art is made by people because ~ excuse the double negative ~ they can’t not make it. Doesn’t matter whether the art they make is good or bad. In your or anyone else’s opinion. They make art because, just like getting up in the morning, there is simply no alternative for them. Even in an extreme case, like van Gogh, anybody out there really think he wouldn't have flicked the switch in exchange for a normal, but art free life? He couldn't, not didn't. And constant use of his messed up mental health by art critics the world over as an explanation of his work is not just a ruse, it’s an insult to his genius.

An infinitely more interesting question is why we need art, what we see in it that is so intrinsically different from what we see just walking around, living our lives. Surely art explains the world to us, but while we can’t argue that context is unimportant, don’t trust history alone for an answer as to why you respond so deeply to one artist’s work, while you are left cold by another’s. In any case, the historical “reasons” we make art change every few hundred (or thousand) years. Since we’ve been keeping track we’ve gone from religion (with God the Über curator) to documentation (Vermeer and the Camera Obscura onward) to a need to explore the psyche (Freud and the Surrealist Movement did a nice tango on this one). For the last few decades art has been obsessed with finding meaning in materialism ~ you can thank Andy Warhol for the soulless Jeff Koons generation. My point is that while context is important, something else is up with our fascination, our need to look at and experience art. Is it finding grace? Is it looking in the mirror? Is it seeing our worst fears exposed?

A few years ago I dragged the family to NYC to see a Gustav Klimt exhibit, 8 paintings and a 120 drawings, at the Neue Galerie, Ronald Lauder’s exquisite private museum on the edge of Central Park. Though one of the most published artists in history, endless squabbles over Klimt’s legacy has made viewing more than one painting at time nearly impossible. The exhibit did not disappoint, but what happened unexpectedly while I was there set me thinking about context in a whole new light. Starting out in poverty, Klimt trained at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts, immediately gaining acceptance and public commissions by Emperor Franz Joseph I. But instead of following a proscribed career, in 1887 he founded the Vienna Secession, a controversial group that encouraged unconventional artistic expression, invited exhibits by foreigners, and published a manifesto that debunked the myth that any one artistic style ~ especially what was in vogue at the time ~ should rein supreme. In short, at the turn of a century that would see two world wars change the map of Europe and, not least, the direction of art forever, Klimt helped push the envelope. Even when briefly shunned by society ~ his work deemed pornographic by every quarter that had once supported him ~ he defied conventions of the day, broke from tradition and become one of the most successful artists of all time.

-

Towards the end of the day I found myself standing in front of Klimt’s portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. The painting, which had been purchased by Lauder for $135 million ~ the highest price ever paid for a single work at the time ~ depicts a beautiful, fragile Jewish woman engulfed in a gilded, intricately decorated world that we know from history was on the precipice of extinction. Lush, subdued color draws the viewer into a universe that cossets yet distinguishes the female form from the fabric of her history. Light skims off the surface of burnished gold leaf, while intricate ornamental detail is eloquently rendered with flowing sinuous lines. Egyptian, Byzantine, Japanese influences, arguably all present, are subsumed by techniques that speak to no known style at all. What seems a sharp edged nod to a Dürer engraving catches in the light and disappears, only to be replaced by a soft tonal mosaic that brings ~ of all people ~ the neo-impressionist Seurat to mind.

As I stood there, a nine-year-old girl who had pulled away from her mother in another gallery came to stand beside me. While all these thoughts were going through my mind, she shifted uncomfortably from side to side. Like it, I asked? Yeah, she said, gnawing at her sleeve, but why is she so sad? Is she, I countered, to which the girl’s eyes, which had been darting around the canvas, looked directly into mine and held for a good five count ~ eons for a nine year old. The only thing free of her body is her mind, she replied. A non-contextual response, to be sure, but she had nailed it. In that moment, somewhere between the two of us, Klimpt’s ghost stirred.

In a few week’s time the question of context will become particularly relevant as the studio mounts Susan Preston’s “One Button Off,” the last show of this exciting and transitional year for us. Susan is one of the most well known and ~ though she would be the last to admit it ~ beloved members of our community. She and her husband Lou have created, in Preston of Dry Creek Farm and Winery, a living agrarian document that eloquently tells a deeply political story which has been instrumental in helping to inform Sonoma County’s embrace of sustainability. The edible gifts of their working farm, which exist so successfully alongside their vineyards, winery and tasting room, have also helped expand a previously limited viticultural agenda for Sonoma that was up to now scarily Napa bound. If you’ve visited the winery, walked the grounds, been lucky to share in their hospitality on any Guadagni Sunday or at any one of a number of public events they host, you cannot have missed how a refined artistic presence infuses everything they do. We live in a county where great wealth has spawned many extremely beautiful wineries, but few speak so fully of an independent artistic vision.

In a few week’s time the question of context will become particularly relevant as the studio mounts Susan Preston’s “One Button Off,” the last show of this exciting and transitional year for us. Susan is one of the most well known and ~ though she would be the last to admit it ~ beloved members of our community. She and her husband Lou have created, in Preston of Dry Creek Farm and Winery, a living agrarian document that eloquently tells a deeply political story which has been instrumental in helping to inform Sonoma County’s embrace of sustainability. The edible gifts of their working farm, which exist so successfully alongside their vineyards, winery and tasting room, have also helped expand a previously limited viticultural agenda for Sonoma that was up to now scarily Napa bound. If you’ve visited the winery, walked the grounds, been lucky to share in their hospitality on any Guadagni Sunday or at any one of a number of public events they host, you cannot have missed how a refined artistic presence infuses everything they do. We live in a county where great wealth has spawned many extremely beautiful wineries, but few speak so fully of an independent artistic vision.

What we haven’t yet seen, though it has been much anticipated, is a full viewing outside the framework of their family endeavors of Susan Preston’s work as an artist.

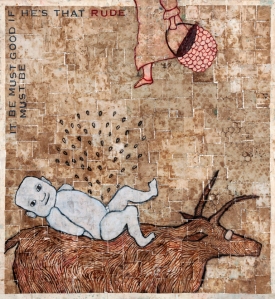

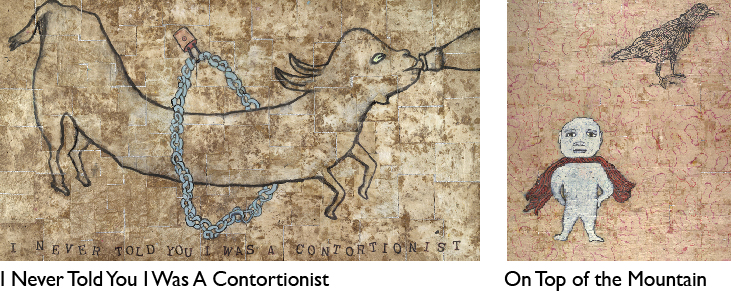

The one-woman show will consist of 14 pieces. The hallmarks of past work will be there ~ the use of wordplay and talisman; the almost mystical transformation of the most common materials ~ but there is a great deal more here as well. A sense of universal themes with rousing, if slightly disturbing narratives. Susan Preston has what I can only describe as a lovers gaze for the animal/people that live in her world, an understanding of sensuality as distinct from gender, a belief that a battered nature is still capable of rocking us to sleep at night. This is a world where fools are kings and art has all the power of the confessional.

The greatest thing about starting with the premise that art need not document anything other than itself is that it enables the viewer to cauterize the aesthetic experience, allowing all the blood to flow back into what you have in front of you. This, at the end of the day, is really all you need to react, feel, reject, or love a work of art. While it may be hard to separate the Susan Preston for whom all actions have consequences (the better to eat you my dear) with Susan Preston, the artist, go for it. The exhibit, which opens on November 10th will run through December. Oh, and don’t forget to bring a nine year old if you happen to have one lying around.

(originally posted November 10, 2010)

Simple lines…complicated faces, the man next to me mumbled. He was talking to himself, but I followed his gaze to a poster across the underground track on the wall just beyond where we were standing, waiting for the train. London was awash in great art shows that winter but the Giotto Exhibit, which the poster was touting, was not high on my list. Religious painters are not my thing really. Yet once the stranger had drawn my attention to the image of the Madonna and child I found I could not look away. Beneath a film of soot the face of a woman who lived centuries before me glowed with incandescent dignity. I felt a better person just being in the same space with her.

Simple lines…complicated faces, the man next to me mumbled. He was talking to himself, but I followed his gaze to a poster across the underground track on the wall just beyond where we were standing, waiting for the train. London was awash in great art shows that winter but the Giotto Exhibit, which the poster was touting, was not high on my list. Religious painters are not my thing really. Yet once the stranger had drawn my attention to the image of the Madonna and child I found I could not look away. Beneath a film of soot the face of a woman who lived centuries before me glowed with incandescent dignity. I felt a better person just being in the same space with her.

I thought about that moment a few weeks back as Susan Preston and I moved through her studio on West Dry Creek looking through a collection of paintings that would comprise her one-woman show at Studio Barndiva, which opens November 10th. It may seem like a stretch to compare the work of a woman living today in a small farming community in Northern California with a man who, in wrestling with how to present the human form realistically on a flat surface, developed his own language for three-dimensional space that changed the course of art history. But that’s the thing about remarkable art: its capacity to capture the singular attributes which make us human transcend both time and providence.

Susan Preston is also an artist who begins with an extremely shallow picture plane that she fills, sparely, with ‘naïve’ characters who challenge our notion of what it means to be spiritually relevant. Whereas artists of Giotto’s time painted from a place infused with religious certainty, Preston, a woman very much of our time, poses a series of complex moral dilemmas. She does this through the development of a mixed-media/mixed-message language that is both literary and textural, resulting in work that, very much like the great Italian master, leaves us believing that the spiritual is ever present.

Take the half naked woman sheltering beneath the waves of Just Drops, Really. Is she the artist viewing history from a distance, or mother nature herself surreptitiously controlling the faceless monks as they make their Canterbury-like way down the mountain, catching rain drops any which way they can? She views the scene with a curious detachment from her self-contained envelope, neither strident nor embarrassed in her nakedness which, despite her age, radiates a rakish charm. Step away from the canvas and you are left contemplating an utterly contemporary question Giotto never had to consider: resources and who controls them. This confrontation without violence is a recurrent Preston theme, one that hints, if not confers, contemplative power.

This is especially true of her babies. These old souls, wise as Buddhas, complacent as cool California dudes, resonate without having to interact with the spare natural order that surrounds them. The caped baby in On Top of the Mountain and little boy on the back of a yak in Upward Tears are all but oblivious to the crow and farm woman who respectively share their world, yet the artist manages to convey that a powerful connection exists between them. The babies of Heaven of the Milk Tree pay little or no attention to the forbidding tree that dominates their landscape, yet their direct but unreadable expressions challenge the viewer to wonder if those dripping fruits which loom above them are filled with milk, or poison (life-giving or deadly). I Can’t Decide, the artist avers, in the title of Milk Tree’s companion piece, leaving us forced to engage with the work on yet a deeper level if we want to arrive at an answer. Which, I would hazard a guess, is precisely what she had in mind.

As for the Preston women, indecision reigns here as well. Motionless while dangerous insects creep into their hair (Hold Still), sanguine and naked in the face of traveling monks, (Just Drops, Really), even with a spike coming out of the head (We’ll Never Do That Again) they persevere with lacerating visual humor co-joined with word play used subversively in the title, or directly written onto the canvas. Whatever the animal is in One Button Off, it is surely female, and dressed for tea and sherry with Dottie at the Algonquin. With Comb Your Hair Jezebel the absent Jezebel, represented by two suspended combs, tines facing inward, answers the exhortation (by her mother?) not with words, but with a solid wall of black that vibrates affirmation in the negative. Black is often used as a conduit for Preston’s question and answer games. Take the portrait of the woman who dominates We’ll Never Do That Again, who for all the nostalgia implied by the use of the silhouette is not only disconnected from her body, but has that alarming bolt driven straight into her elegantly coiffed head. Which of the two calamities that has befallen her will “We” not do again?

As for the Preston women, indecision reigns here as well. Motionless while dangerous insects creep into their hair (Hold Still), sanguine and naked in the face of traveling monks, (Just Drops, Really), even with a spike coming out of the head (We’ll Never Do That Again) they persevere with lacerating visual humor co-joined with word play used subversively in the title, or directly written onto the canvas. Whatever the animal is in One Button Off, it is surely female, and dressed for tea and sherry with Dottie at the Algonquin. With Comb Your Hair Jezebel the absent Jezebel, represented by two suspended combs, tines facing inward, answers the exhortation (by her mother?) not with words, but with a solid wall of black that vibrates affirmation in the negative. Black is often used as a conduit for Preston’s question and answer games. Take the portrait of the woman who dominates We’ll Never Do That Again, who for all the nostalgia implied by the use of the silhouette is not only disconnected from her body, but has that alarming bolt driven straight into her elegantly coiffed head. Which of the two calamities that has befallen her will “We” not do again?

Yet for all the unsettling questions that go unanswered in these paintings, they are not sad pictures, not by a long shot. With an irreverent and politically charged sense of the absurd the artist creates a strange band of characters and anthropomorphic animals that challenge our perceptions of what it really means to be alive, to be hungry. They also give us the chance to reflect on a universal truth: no sooner do we gain command of life than circumstances beyond our control will no doubt shake the ground we stand on.

This shifting sense of reality is made manifest visually with Preston’s collage technique which relies heavily on the use of distressed recycled paper. The brown paper ~ a supermarket variety which we all know so well from a lifetime of carting groceries home ~ is put through a time consuming process in which she buries, drowns, irons, and over paints it with watery gauche, the better to see through. This alchemy transforms the uniform brown into a gorgeous tonal pallet that brings to mind sun-baked earth, cracked leather, butterscotch, wheat, parchment, and sand. Under her hand, ordinary paper becomes all but unrecognizable, yet somehow retains the very essence of itself.

As wonderful as her use of paper is, it is but half a visual pas de deux that takes an archaic reference of reflective gold, once used for its resplendence and to confer both spiritual and political power, and turns it on its head. Here, beneath a cracked pavement of cut and torn paper, a silvery world beckons. The inference, that there is nothing to stop us finding magic in the most prosaic of materials (in this case chewing gum wrappers) goes well beyond the trope that all that glitters is not gold. Viewed straight on, the juxtaposition of textural organic earth tones edged with silver registers as a flat opaque surface, but the moment the viewer commits ~ an eye moving across the canvas, a shift of the body ~ light catches along the irregularly cut edges of paper igniting a grid of luminous intersecting lines, electrifying the entire canvas.

As wonderful as her use of paper is, it is but half a visual pas de deux that takes an archaic reference of reflective gold, once used for its resplendence and to confer both spiritual and political power, and turns it on its head. Here, beneath a cracked pavement of cut and torn paper, a silvery world beckons. The inference, that there is nothing to stop us finding magic in the most prosaic of materials (in this case chewing gum wrappers) goes well beyond the trope that all that glitters is not gold. Viewed straight on, the juxtaposition of textural organic earth tones edged with silver registers as a flat opaque surface, but the moment the viewer commits ~ an eye moving across the canvas, a shift of the body ~ light catches along the irregularly cut edges of paper igniting a grid of luminous intersecting lines, electrifying the entire canvas.

Though they have the power to haunt you for days, these are not, to my mind, personal pictures. The artist herself remains very much a mystery to the viewer. The one exception is Goodbye Pina, painted after the death of the great dance choreographer Pina Bausch. With an initial nod to Giotto’s God in the heavenly direction Pina’s body takes in her contorted dance of death, Preston then refuses to relinquish her beloved muse to an idealized heaven. Pina dances into eternity only after she has risen through an undulating landscape and crossed over into a searing black monolithic sky. Relieved of her pain and made whole again, the power of this simply drawn figure in danceflight is remarkable.

A versifier of the highest order (she could easily have been a poet) words are used to great effect throughout the pieces in One Button Off. We Killed The Wrong Twin begs two questions: our complicity, and why the wrong twin needed to be killed in the first place; Bring It Back may be a refrain from the kid issuing the baby bottles from his mouth, or again, from the artist to the viewer about our inability to feed ourselves in what Preston, in her other life as a organic farmer, knows full well are dire times. The elongated goat in I Never Told You I Was A Contortionist, clearly is, while the caped baby in On Top Of The Mountain, clearly is not. Are these titles lies, or, by being put on notice to suspect all words, are we simply being cajoled into making new meanings from them? Take your pick. By consistently sneaking up on the viewer and whispering discreet possibilities in our ear, on both an intellectual and a sensual level Susan Preston has made it clear in this collection that we are free to consider all options. Art that exhibits this level of profundity seeks not only to claim the epicenter of our attention, but creates its own morally complex force field. To the man in the train station I would say “Simple faces, complicated lives.” Much like our own.

(Originally posted November 17, 2010)

All of Healdsburg turned out for the opening night of Susan Preston's one woman show ~ One Button Off~ last Friday evening. Thanks to an insane Barndiva cocktail called The Contortionist and a surfeit of always wonderful Preston wines, no one seemed to mind the wall to wall crowds. (We apologize to any of our guests who did not get to taste the spicy chopped Mediterranean salad we served on Lou's baguettes or our crispy tempura string beans.)

(originally posted October 6, 2010)

I don’t know how many times I re-read Raymond Carver’s short story collection “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” over the years, but the spine of the book eventually fell apart if that tells you anything. Carver had that particular kind of talent that could surgically slice through the emotional muscle we build up over our hearts, all the better to prod at what lies below. But while I still crave stories that seek to answer what for me has been one of life’s most mystifying question ~ what DO we talk about when we talk about love ~ with respects to Carver, I’m tired of quiet denouements that artfully foretell a future in which lasting true love is pretty much a hopeless proposition. I’ve spent a lifetime mucking about in the name of love, licking my wounds, acknowledging my mistakes. If all that doesn’t confer wisdom, at least let me celebrate the fact that it speaks to a enduring optimism of the heart.

When I was younger I was epically naïve on this (and sadly many other) subjects. I had the requisite young person’s immediate apathy towards any marriage that smacked to me of convention, rejecting the kind of relationship where after you stripped away the holidays, martini hour and whose responsibility it was to pick Jimmy up from Judo there was no deeper intellectual connection to carry the day once the children had grown. I was sticking too closely to the Ibsen script by only defining ‘convention’ as some narrow set of rules for conduct dictated solely by the mores of the day. Convention ~ old fashioned values ~ also means following a code of honor that often puts character above passion, especially bad news for my horny generation. This didn’t occur to me then, not even when friends of my parents started to get divorced in blockbuster numbers. It was easier to blame the institution.

My generation held out the hope that through equality of the sexes we might remedy what had been wrong with marriages that came before us, but we swung the pendulum too far in the other direction. Trying to create an agenda of shared interests, even going so far as to swap roles like wage earning and child rearing, we too often fell into over analyzing every interaction, awarding stars for good behavior, taking away privileges when we fell short. Feelings, instead of providing a way into the loved one's psyche, all too often became the shield we used to protect ourselves. As often follows when one gets ready for battle, after the shield came the sword.

My generation held out the hope that through equality of the sexes we might remedy what had been wrong with marriages that came before us, but we swung the pendulum too far in the other direction. Trying to create an agenda of shared interests, even going so far as to swap roles like wage earning and child rearing, we too often fell into over analyzing every interaction, awarding stars for good behavior, taking away privileges when we fell short. Feelings, instead of providing a way into the loved one's psyche, all too often became the shield we used to protect ourselves. As often follows when one gets ready for battle, after the shield came the sword.

So here is a marital parable for our times. When Earl Fincher met Myrna Hall 52 years ago, he wasn't looking for a meaningful relationship. He was a 20- year old boy intent on sowing his wild oats. She was a beautiful 15-year old with a wide open heart. They met a dance. He had no money and few prospects. There was no conscious meeting of the minds, no existential conversations or résumé sharing, just an honest physical attraction they could not ignore. Marriage was the last thing on either of their minds. Earl worked long hours, just as he had done since he was 8 years old, the year his parents left Missouri for a protracted hardscrabble journey west that eventually landed them in California, in the small farming town of Healdsburg, doing migrant work picking in the fields.

Possessed of a relentlessly curious mind, Earl has an uncanny ability to think endlessly on all manner of things that fall into the ‘how to build a better birdhouse’ category. But then, as now, when it comes to what the rest of us consider the ‘big’ issues, like wrong from right, he does not have to think much at all. The way he sees it, there are the things in life you have to wrestle to the ground to figure out, and then there is the stuff you should just know. He knew what to do when he took measure of Myrna. He married her.

If Myrna was scared starting out so young in life with a man that had but $11 in his pocket ($10 after they paid the preacher) she is not saying so now. They met in Spring, by Christmas she had given birth to their first child. Life was good but hard. Only once did they have to break Earl’s cardinal rule ~ never rely upon anyone else ~ and then only to stay with Myrna’s family for a few weeks during a particularly rough time. They saved every dollar, working and living up at Michel-Schlumberger, followed by a stint at Gallo. A lucky conversation Earl overheard one day looking for work brought him to the gates of the mill in Healdsburg just as construction in the area was taking off. With Earl’s work ethic, it’s not surprising a one-day job turned into a 26 year career.

If Myrna was scared starting out so young in life with a man that had but $11 in his pocket ($10 after they paid the preacher) she is not saying so now. They met in Spring, by Christmas she had given birth to their first child. Life was good but hard. Only once did they have to break Earl’s cardinal rule ~ never rely upon anyone else ~ and then only to stay with Myrna’s family for a few weeks during a particularly rough time. They saved every dollar, working and living up at Michel-Schlumberger, followed by a stint at Gallo. A lucky conversation Earl overheard one day looking for work brought him to the gates of the mill in Healdsburg just as construction in the area was taking off. With Earl’s work ethic, it’s not surprising a one-day job turned into a 26 year career.

By 1970 they had finally saved enough to put a down payment on some land. It was 3 ½ acres on Chalk Hill Road for $7,000, a price that was not as cheap as it sounds today ~ certainly not for them. But they managed to pay it off and finance a loan to build a house. It is the house they still live in, raising their family of five, year by year expanding the verdant patchwork of raised beds and fields from which they now feed their many loyal customers and restaurants like Barndiva. It is a source of great pride to them that they paid off that 30 year mortgage ~ though it took them every one of those 30 years ~ just like they said they would.

Early Bird's Place is laid out in a jumble of outbuildings, all with a different purpose, all filled with inventions Earl has designed over the years. Myrna calls the stuff that fills the ranch house, garage, potting and gourd drying sheds and chicken coops ‘creative clutter’. She closes her eyes, sighs and smiles when she says the word creative, adding that Earl is a man incapable of throwing anything away. It is something she both hates and loves about him, in unequal measure. Unequal is the operative word because, according to Myrna, love is never equal at any given moment in time. After more than fifty years together they have seen all the fault lines in each other; it no longer matters who is right or who is wrong. So long as I always put Earl first in my thoughts, she will tell you, and he does the same for me.

A few weeks back I visited them at the farm with Drew Kelly, a talented young photographer who is working to help me document Barndiva’s ties to a cadre of local farmers. It was a joy to see them together as I usually only ever see Myrna alone when she drops off produce and eggs at Barndiva's kitchen door. It struck me ~ as it must folks that see them together every week at Healdsburg’s Farmer's Market ~ how completely they compliment each other without either losing a beat on what makes them so interesting as individuals.

There is true adoration in their banter, which is played out in the physical dance they do as they move through their many rooms and linked gardens. Earl is short and wiry, these days he walks with most of his weight held high up in his shoulders, steering in a specific direction until something interesting catches his eye and he changes course. Myrna is rounder, more kinetic as she moves, with an almost tendril quality in the way she constantly reaches out with the part of her that is most vulnerable, fragile wrists encased in protective bands where repetitive strain injury has taken its toll. When the distance between them grows too great she weaves back to him in looping circles. In this way they trade off who leads and who follows.

This then is the secret of their marriage: it doesn’t matter who leads or who follows. By not constantly reassessing how the other might be falling short, or what might be missing from their marriage, they never made the fatal mistake of taking what they did find in each other for granted. If it always wasn’t this way, it hardly matters now. I learned to button my lip early on, Myrna will tell you, the important thing is to be patient, to know that marriage has a way of balancing out. There’s nothing I wouldn’t do for her, Earl will tell you. She’s is my life’s helpmate. For a man who understands the nature of life as hard work, there is no greater compliment he could give.

(originally posted September 29, 2010)

Healdsburg made a joyful noise on Saturday night ~ especially on our part of Center Street where 200 elegantly dressed people of all ages came together and kissed, wept, drank, ate, laughed, told stories, then lost their shoes and danced their hearts out. Our weddings are always very special, but something else was in the air as well. As if the brief return of a warm night coupled with the sense that only a few weeks are left of summer heightened the mood so it swelled beyond the happiness felt by this particular couple and their families and friends. It reminded me how important it is going to be in the coming year to express delight whenever we can. We will continue to face seemingly insurmountable problems ~ a faltering economy, an ailing ecology, a paucity of leadership ~ that history has placed at our door. Most solutions will come in tiny packages. All but a few will seem to take too much time. Many of us reading this will not be around to see how it all plays out for our children and grandchildren. But we are in the game right now, and each of us with a powerful role to play. With the stakes so high, we need to keep from feeling overwhelmed. It’s essential we stop when we can to acknowledge that good things are still happening, though sometimes they need a jump start.

The first thought we came up with to keep the parties going ~ stay tuned for lots more ~ was to open the Gallery for musical evenings, films, talks and fun cocktail parties of any size. We will waive all facility rental fees to make use of the space more affordable. Our menus will be keenly priced, but will continue to be sourced locally and sustainably. Our farmers need to feed their bottom line, as do we, but we want Studio Barndiva to feed something else as well ~ a sense that as a community we have a great deal to be thankful for.

We like the French word soirée, even though it sounds a bit poncy, because it really does capture what we’d like to see happen in the Studio. To wit: “An evening party or social gathering esp. one held for a particular purpose” yes, that hits the nail on the head! Besides, it rhymes with archway, which is nice. Sometimes friendship alone pulls us through to the next courtyard in life, sometimes it’s music, or the spoken word. The point is to keep moving in an interesting direction. Yet real social contact is precisely what our all-consuming electronic media is robbing us of. What’s most important when we come together in groups, after the work of the day is done, is often simply that we are together. And while it’s great when you know people at a party, often it’s more exciting when you don’t. In a community our size ~ with so many interests and passions and so much talent to express them ~ it almost doesn’t matter what draws you away from the campfire of your hi-def screens and out to the town square. Your presence alone has the power to redefine the space, and claim it. Not knowing the outcome is part of the magic.

Of course it helps when there is great food and drink ~ which we will happily provide. When Ryan first came to us we weren’t sure how he would feel about all our weddings and special events. Lots of chefs look down on events, understandably. It’s not just the amount of work that goes into coordinating them. From a chef’s point of view, because of the timing and the sheer number of plates, most often they don’t showcase a chef’s talent in the way fine dining does.

Taking his cues from Lukka, whose joie de vivre is legendary, Ryan has fun with the menus, be they family style or comprised of many wine paired courses. He approaches a glitzy Oscar Night or a serious dinner where each course is paired with the dirt it was grown in with the same intensity, and as his talent blossoms it reflects on each and every farmer partner. Even for those working the events the sheer exuberance and style of our parties is contagious. By summer’s end we will have sent thousands of people back to their own cities and towns across the country talking about what’s going on in Healdsburg. Not just Barndiva ~ but the connection they made here with the surrounding community. Hopefully it sent them looking to recreate parts of that experience closer to home.

By making the story of local sourcing the point of our food, we haven’t relegated Ryan’s talent anymore than Bonnie Z’s, whose gift for arranging flowers is sometimes subsumed by the sheer extravagance of her locally grown blooms. Talent and product become indispensable to each other, and for the end user, indistinguishable. We all live in cultivated landscapes, in self-curated spaces. What we choose to seed and grow and prune is up to us. If only a fraction of our wedding guests go back to their hometowns and seek out a Farmer’s Market, that’s a fraction more than had the desire to do so when they sat down and unfurled their napkins on a warm summer night beneath the fairy lit arches in our gardens.

But make no mistake: Joy is the carrier of that message. And Joy, while clearly not in abundance these days, does not need a wedding to thrive.

So listen up: If you own a business and want to say thanks for a year of hard work (with another yet to come) or are a group of friends wanting to meet up to raise high the roof beams, we want to make Studio Barndiva ~ and the food and drink we serve ~ available to you. While we hope you will join us for some of our upcoming scheduled events (first up: the opening party for the much anticipated Susan Preston Exhibit: One Button Off) consider this an invitation to think up your own reason for a soirée in the coming months ~ rhyme it as you will.