Handblown glass from Sugahara, one of the finest glass blowing companies in Japan.

Barware $30 Drinking Glasses $29

Viewing entries in

Gallery

Handblown glass from Sugahara, one of the finest glass blowing companies in Japan.

Barware $30 Drinking Glasses $29

How To Make Your Own Chicken Coop, circa 1923

How To Make Your Own Chicken Coop, circa 1923

Bastidor Santos mannequins were traditionally paraded around the streets in Spain during religious holidays, adorned with elaborate costumes.

Hand carved Narwood, these are based on an original Spanish Colonial design:

Bust $290

Mannequin $300

Bastidor Santos mannequins were traditionally paraded around the streets in Spain during religious holidays, adorned with elaborate costumes.

Hand carved Narwood, these are based on an original Spanish Colonial design:

Bust $290

Mannequin $300

Just in:

Manok Cohen

The Cloud

40 x 48

$2900

Just in:

Manok Cohen

The Cloud

40 x 48

$2900

(originally posted November 17, 2010)

Ever wondered what it looks like above Barndiva? Here's your chance. Great images and recipes by Chef Ryan accompany the article by Sarah Lynch in California Home + Design Magazine.

Photography by Drew Kelly and Brad Gillette

LEFT: Studio Barndiva’s eclectic offerings include local artwork and imported accessories, but the blue fireplace—adorned with a Magritte-worthy “It is not a fireplace”—makes it clear that visitors can always expect a surprise. TOP RIGHT: Jil and Geoffrey Hales built their barn (right) from scratch.

The perfect evening out brings together three elements: a delicious meal, a warm atmosphere and lively conversation. For Jil Hales, the proprietor of Healdsburg’s Barndiva restaurant, the bar is set significantly higher because the bar is where it all began.

“We came to Healdsburg eight years ago, after raising our kids in the U.K. and living in San Francisco for a few years,” says Hales, a Los Angeles native married to Geoffrey, a Brit, who brought his hardwood flooring company to the U.S. “What this town was missing was a world-class bar—a place to get a cocktail and a bite to eat late at night.”

LEFT: The kitchen island in the pied-à-terre was fitted with fluorescent lighting and colored gels as a prototype for the restaurant bar. RIGHT: A farm-worthy monitor, painted salmon pink, in the center of the ceiling will one day be accessed by a catwalk.

While the Hales were dividing their time between London and a fruit farm in Anderson Valley that Jil has owned for 30 years, they bought a property just off the town square in Healdsburg and built a two-story barn from the ground up. Downstairs, the bar and restaurant serve the best cocktails in town and an ever-evolving menu of farm-to-table dishes. Upstairs is the Hales’ pied-à-terre. Acting as general contractor and chief designer of the barn was an all-encompassing project, and Jil lived up to the nickname her friends had given her when she first moved to Anderson Valley: the Barn Diva.

Adapting the name to her new venture, Jil’s restaurant suitably hits a few high notes. From the outside, the building suggests a familiar rural vernacular—it’s a single structure with richly stained board-and-batten siding. Inside, the towering space is a sophisticated mix of travertine floors, wood tables, a colorfully lit bar and cream-colored walls adorned with modern art and antique farming tools. Out back, an enclosed garden is set with tables, big rustic sculptures and a trickling water feature; overhead mulberry trees are draped with twinkling fairy lights and a heritage black walnut offers dappled shade during the day.

FROM LEFT: The Cor-Ten steel and neon lights in Barndiva’s sign hint at the owners’ modern sensibilities; Studio Barndiva represents local artists such as painter Laura Parker and wire sculptor Ismael Sanchez; floor-to-ceiling drapes, formal flower arrangements and streamlined drum shades are just some of the sophisticated designs Jil chose for the restaurant; before coming to Barndiva

The pied-à-terre upstairs, which is accessed through the front door tucked alongside the restaurant’s entry patio and up a Dan Flavin-esque staircase with rainbow fluorescent risers, is even more of a surprise. It feels like a loft in Tribeca rather than a barn apartment in Sonoma County. The voluminous main room is centered on an oval dining table surrounded by red leather Eames Executive chairs. On one side a 16-foot-long kitchen island is topped with another fluorescent-lit bar (the prototype for the bar downstairs). The kitchen itself is an updated take on the European unfitted kitchen, with open storage, several sinks and a formidable black-enamel Lacanche range. A built-in bar adorned with Jil’s favored Tunisian ironwork, more classic midcentury furniture and artwork collected from around the world complete the scene in the main space. On one end is a guest bedroom and office mezzanine, and on the other is a master suite.

Two-and-a-half years after completing the barn, the restaurant was bustling on evenings and weekends, and Jil was ready to raise the bar even higher. The Hales’ life in Healdsburg had become increasingly focused on the community around them as they supported local vintners and farmers. But Jil’s passion for art and design needed an outlet, and the four walls of the restaurant were filled. So in 2007 she opened a gallery next door in a space that was formerly an opera house. Artists & Farmers, as it was originally called (now Studio Barndiva), was a place to celebrate and sell the art and designs she discovered locally or on her many travels. On display is an assemblage of Hales’ own lighting made from Tunisian architectural salvage along with locally crafted paintings, wire sculptures, blown glass, reclaimed wood furniture, imported gifts and accessories. “I don’t want to show things that can be easily found somewhere else,” says Hales, pointing out one exception: aselection of John Derian back-painted glass plates. “I know he’s in lots of other shops, but he’s a friend.”

LEFT TO RIGHT: The restaurant’s back patio features pendants that Jil fashioned from Tunisian window guards; fluorescent lights show up at the bar, where a circular backlit inset mimics the two round windows at the top of the building; the entrance to the private residence is marked by a dramatic glowing staircase; the weather in Healdsburg makes it ideal for outdoor wedding receptions.

Behind the gallery is yet another garden. This one is filled with raised vegetable beds, outdoor sculpture and a table large enough to seat 200 under an armature designed for a canopy of mini-globe lights. Like the garden on the other side of the fence, the setup begs for a modern country wedding and it’s been a popular spot for such events since it opened. In fact, Geoffrey and the couple’s eldest son, Lukka, run Barndiva’s event and hospitality business, and they’re now averaging 60 weddings a year. The Hales have also taken over management of the nearby Healdsburg Modern Cottages, four nightly cottages authentically furnished with pieces by Eileen Gray, George Nelson, and Ray and Charles Eames.

LEFT: The humble facade of Barndiva belies the stylish elegance of the experience inside. RIGHT: An outdoor area behind the gallery is attached to the restaurant’s garden through a gate and is a popular spot for wedding receptions.

In her mission to open a world-class bar in this sleepy town, Jil has elevated the creation of the perfect evening to an art form. “I went for the type of environment where I would want to share a meal or toast a special occasion with friends,” she says. “If something doesn’t come from the heart, it just doesn’t work. If you’re not authentic, you’re running on fumes.”

Sitting under twinkling lights, as a parade of seasonal dishes made by Thomas Keller–trained chef Ryan Fancher, original cocktails and wine selected by the in-house sommelier passes by, it would be hard to argue against that.

Both of these recipes make the most of fruit and vegetables in late summer or early autumn, when ingredients are at the height of their season. They are great dishes to source at a local farmers market.

Barndiva’s Heirloom Tomato & Compressed Watermelon Salad Serves 4

1 medium watermelon 1 tsp. lemon verbena 1 large golden beet 1 large Detroit dark-red beet 6 heirloom tomatoes 2 Tbsp. sweet basil 4 Tbsp. Spanish sherry vinaigrette Salt and freshly ground pepper 1 cup purslane (optional) 2 Tbsp. crystallized ginger, diced 2 red radishes

Spanish Sherry Vinaigrette 1 cup grape seed oil 1/3 cup Spanish sherry vinegar A pinch of salt, sugar and freshly ground pepper

• The Watermelon - The night before or a few hours before serving, cut into large cubes and sprinkle with the chopped lemon verbena. Wrap tightly in plastic wrap and refrigerate. • The Beets - Cover with 2 cups water, 1 Tbsp. butter, 1 clove garlic and a sprig of thyme. Cover and cook at 350° for 3 hours. Cool and slice. • The Heirloom Tomatoes - Slice them thickly and mix them in with the chopped sweet basil. In a bowl, whisk together all of the ingredients for the vinaigrette. Bathe the tomatoes in 4 tablespoons of the vinaigrette for 30 minutes or more. Season with salt and freshly ground pepper. • Assemble - Stack the tomatoes, largest one on the bottom. Arrange the watermelon. Dress the beets in the bathing vinaigrette, season with salt and pepper, and plate. Sprinkle ginger and thinly sliced radishes over the dish. Dress the purslane, and add it to the dish to finish.

Herb-Roasted Local Halibut Serves 4

8 baby artichokes 2 Tbsp. canola oil 4 cloves garlic 2 springs rosemary Salt and pepper 20 fava beans 1 zucchini 1 gold bar squash 5 lbs. Roma tomatoes 15 Toy Box cherry tomatoes 2 Tbsp. extra virgin olive oil 4 6-oz. halibut filets 1 Tbsp. butter 1 cup tempura batter 4 squash blossoms

Tempura batter 1/2 cup flour Corn starch 1 tsp. baking powder 1/2 cup sparkling water Salt

• The Baby Artichokes - Peel the outside layers to reveal the heart. In a hot pan, roast the artichokes with canola oil, garlic and rosemary until soft. Season with salt and pepper. • The Fava Beans - Peel the favas, and cook them in boiling salted water for one minute. Let cool. • The Summer Squash - Cut the zucchini and squash into diamond shapes, and cook them just like the fava beans. • Vierge sauce - Puree the tomatoes, and strain the clear liquid from the tomatoes through a clean kitchen towel. In a saucepan over medium heat, reduce the liquid by half, and season with salt and pepper. Drizzle extra virgin olive oil. • Halibut - In a hot sauté pan, sear the fish until golden brown, being careful to not overcook. Baste with butter, garlic and rosemary. • Assemble - Pool the sauce in a bowl or shallow plate. Arrange the vegetables in the sauce, and nestle the halibut in the middle. In a bowl, mix the tempura batter’s ingredients, and dress the blossom lightly with the tempura batter. Fry in 350° oil until golden, and place on top of fish.

(originally posted October 13, 2010)

The compulsion to make art has been with us for 17,000 years. For most of that time, the foremost question asked of the artist (perhaps second only to where’s the rent) has been why do you do it ~ where does this unstoppable urge to create come from? It’s a fascinating question especially if you’ve never had the calling, but beware the loquacious artist ~ Picasso pops to mind ~ who can come up with what sounds like a dazzling answer to what is ultimately a goose chasing question.

“You might as well ask me why I get out of bed in the morning,” an artist friend once explained, to this day the most refreshingly honest answer I’ve heard. By and large, art is made by people because ~ excuse the double negative ~ they can’t not make it. Doesn’t matter whether the art they make is good or bad. In your or anyone else’s opinion. They make art because, just like getting up in the morning, there is simply no alternative for them. Even in an extreme case, like van Gogh, anybody out there really think he wouldn't have flicked the switch in exchange for a normal, but art free life? He couldn't, not didn't. And constant use of his messed up mental health by art critics the world over as an explanation of his work is not just a ruse, it’s an insult to his genius.

An infinitely more interesting question is why we need art, what we see in it that is so intrinsically different from what we see just walking around, living our lives. Surely art explains the world to us, but while we can’t argue that context is unimportant, don’t trust history alone for an answer as to why you respond so deeply to one artist’s work, while you are left cold by another’s. In any case, the historical “reasons” we make art change every few hundred (or thousand) years. Since we’ve been keeping track we’ve gone from religion (with God the Über curator) to documentation (Vermeer and the Camera Obscura onward) to a need to explore the psyche (Freud and the Surrealist Movement did a nice tango on this one). For the last few decades art has been obsessed with finding meaning in materialism ~ you can thank Andy Warhol for the soulless Jeff Koons generation. My point is that while context is important, something else is up with our fascination, our need to look at and experience art. Is it finding grace? Is it looking in the mirror? Is it seeing our worst fears exposed?

A few years ago I dragged the family to NYC to see a Gustav Klimt exhibit, 8 paintings and a 120 drawings, at the Neue Galerie, Ronald Lauder’s exquisite private museum on the edge of Central Park. Though one of the most published artists in history, endless squabbles over Klimt’s legacy has made viewing more than one painting at time nearly impossible. The exhibit did not disappoint, but what happened unexpectedly while I was there set me thinking about context in a whole new light. Starting out in poverty, Klimt trained at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts, immediately gaining acceptance and public commissions by Emperor Franz Joseph I. But instead of following a proscribed career, in 1887 he founded the Vienna Secession, a controversial group that encouraged unconventional artistic expression, invited exhibits by foreigners, and published a manifesto that debunked the myth that any one artistic style ~ especially what was in vogue at the time ~ should rein supreme. In short, at the turn of a century that would see two world wars change the map of Europe and, not least, the direction of art forever, Klimt helped push the envelope. Even when briefly shunned by society ~ his work deemed pornographic by every quarter that had once supported him ~ he defied conventions of the day, broke from tradition and become one of the most successful artists of all time.

Towards the end of the day I found myself standing in front of Klimt’s portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. The painting, which had been purchased by Lauder for $135 million ~ the highest price ever paid for a single work at the time ~ depicts a beautiful, fragile Jewish woman engulfed in a gilded, intricately decorated world that we know from history was on the precipice of extinction. Lush, subdued color draws the viewer into a universe that cossets yet distinguishes the female form from the fabric of her history. Light skims off the surface of burnished gold leaf, while intricate ornamental detail is eloquently rendered with flowing sinuous lines. Egyptian, Byzantine, Japanese influences, arguably all present, are subsumed by techniques that speak to no known style at all. What seems a sharp edged nod to a Dürer engraving catches in the light and disappears, only to be replaced by a soft tonal mosaic that brings ~ of all people ~ the neo-impressionist Seurat to mind.

As I stood there, a nine-year-old girl who had pulled away from her mother in another gallery came to stand beside me. While all these thoughts were going through my mind, she shifted uncomfortably from side to side. Like it, I asked? Yeah, she said, gnawing at her sleeve, but why is she so sad? Is she, I countered, to which the girl’s eyes, which had been darting around the canvas, looked directly into mine and held for a good five count ~ eons for a nine year old. The only thing free of her body is her mind, she replied. A non-contextual response, to be sure, but she had nailed it. In that moment, somewhere between the two of us, Klimpt’s ghost stirred.

In a few week’s time the question of context will become particularly relevant as the studio mounts Susan Preston’s “One Button Off,” the last show of this exciting and transitional year for us. Susan is one of the most well known and ~ though she would be the last to admit it ~ beloved members of our community. She and her husband Lou have created, in Preston of Dry Creek Farm and Winery, a living agrarian document that eloquently tells a deeply political story which has been instrumental in helping to inform Sonoma County’s embrace of sustainability. The edible gifts of their working farm, which exist so successfully alongside their vineyards, winery and tasting room, have also helped expand a previously limited viticultural agenda for Sonoma that was up to now scarily Napa bound. If you’ve visited the winery, walked the grounds, been lucky to share in their hospitality on any Guadagni Sunday or at any one of a number of public events they host, you cannot have missed how a refined artistic presence infuses everything they do. We live in a county where great wealth has spawned many extremely beautiful wineries, but few speak so fully of an independent artistic vision.

In a few week’s time the question of context will become particularly relevant as the studio mounts Susan Preston’s “One Button Off,” the last show of this exciting and transitional year for us. Susan is one of the most well known and ~ though she would be the last to admit it ~ beloved members of our community. She and her husband Lou have created, in Preston of Dry Creek Farm and Winery, a living agrarian document that eloquently tells a deeply political story which has been instrumental in helping to inform Sonoma County’s embrace of sustainability. The edible gifts of their working farm, which exist so successfully alongside their vineyards, winery and tasting room, have also helped expand a previously limited viticultural agenda for Sonoma that was up to now scarily Napa bound. If you’ve visited the winery, walked the grounds, been lucky to share in their hospitality on any Guadagni Sunday or at any one of a number of public events they host, you cannot have missed how a refined artistic presence infuses everything they do. We live in a county where great wealth has spawned many extremely beautiful wineries, but few speak so fully of an independent artistic vision.

What we haven’t yet seen, though it has been much anticipated, is a full viewing outside the framework of their family endeavors of Susan Preston’s work as an artist.

The one-woman show will consist of 14 pieces. The hallmarks of past work will be there ~ the use of wordplay and talisman; the almost mystical transformation of the most common materials ~ but there is a great deal more here as well. A sense of universal themes with rousing, if slightly disturbing narratives. Susan Preston has what I can only describe as a lovers gaze for the animal/people that live in her world, an understanding of sensuality as distinct from gender, a belief that a battered nature is still capable of rocking us to sleep at night. This is a world where fools are kings and art has all the power of the confessional.

The greatest thing about starting with the premise that art need not document anything other than itself is that it enables the viewer to cauterize the aesthetic experience, allowing all the blood to flow back into what you have in front of you. This, at the end of the day, is really all you need to react, feel, reject, or love a work of art. While it may be hard to separate the Susan Preston for whom all actions have consequences (the better to eat you my dear) with Susan Preston, the artist, go for it. The exhibit, which opens on November 10th will run through December. Oh, and don’t forget to bring a nine year old if you happen to have one lying around.

(originally posted November 10, 2010)

Simple lines…complicated faces, the man next to me mumbled. He was talking to himself, but I followed his gaze to a poster across the underground track on the wall just beyond where we were standing, waiting for the train. London was awash in great art shows that winter but the Giotto Exhibit, which the poster was touting, was not high on my list. Religious painters are not my thing really. Yet once the stranger had drawn my attention to the image of the Madonna and child I found I could not look away. Beneath a film of soot the face of a woman who lived centuries before me glowed with incandescent dignity. I felt a better person just being in the same space with her.

Simple lines…complicated faces, the man next to me mumbled. He was talking to himself, but I followed his gaze to a poster across the underground track on the wall just beyond where we were standing, waiting for the train. London was awash in great art shows that winter but the Giotto Exhibit, which the poster was touting, was not high on my list. Religious painters are not my thing really. Yet once the stranger had drawn my attention to the image of the Madonna and child I found I could not look away. Beneath a film of soot the face of a woman who lived centuries before me glowed with incandescent dignity. I felt a better person just being in the same space with her.

I thought about that moment a few weeks back as Susan Preston and I moved through her studio on West Dry Creek looking through a collection of paintings that would comprise her one-woman show at Studio Barndiva, which opens November 10th. It may seem like a stretch to compare the work of a woman living today in a small farming community in Northern California with a man who, in wrestling with how to present the human form realistically on a flat surface, developed his own language for three-dimensional space that changed the course of art history. But that’s the thing about remarkable art: its capacity to capture the singular attributes which make us human transcend both time and providence.

Susan Preston is also an artist who begins with an extremely shallow picture plane that she fills, sparely, with ‘naïve’ characters who challenge our notion of what it means to be spiritually relevant. Whereas artists of Giotto’s time painted from a place infused with religious certainty, Preston, a woman very much of our time, poses a series of complex moral dilemmas. She does this through the development of a mixed-media/mixed-message language that is both literary and textural, resulting in work that, very much like the great Italian master, leaves us believing that the spiritual is ever present.

Take the half naked woman sheltering beneath the waves of Just Drops, Really. Is she the artist viewing history from a distance, or mother nature herself surreptitiously controlling the faceless monks as they make their Canterbury-like way down the mountain, catching rain drops any which way they can? She views the scene with a curious detachment from her self-contained envelope, neither strident nor embarrassed in her nakedness which, despite her age, radiates a rakish charm. Step away from the canvas and you are left contemplating an utterly contemporary question Giotto never had to consider: resources and who controls them. This confrontation without violence is a recurrent Preston theme, one that hints, if not confers, contemplative power.

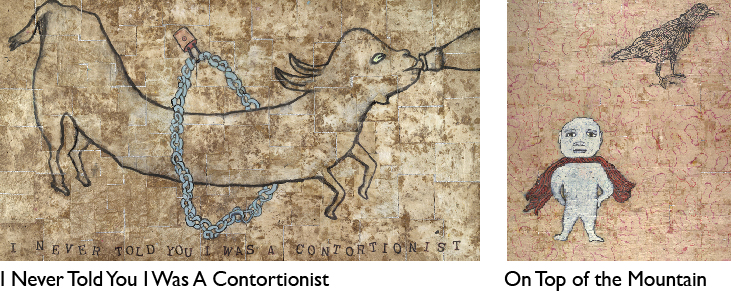

This is especially true of her babies. These old souls, wise as Buddhas, complacent as cool California dudes, resonate without having to interact with the spare natural order that surrounds them. The caped baby in On Top of the Mountain and little boy on the back of a yak in Upward Tears are all but oblivious to the crow and farm woman who respectively share their world, yet the artist manages to convey that a powerful connection exists between them. The babies of Heaven of the Milk Tree pay little or no attention to the forbidding tree that dominates their landscape, yet their direct but unreadable expressions challenge the viewer to wonder if those dripping fruits which loom above them are filled with milk, or poison (life-giving or deadly). I Can’t Decide, the artist avers, in the title of Milk Tree’s companion piece, leaving us forced to engage with the work on yet a deeper level if we want to arrive at an answer. Which, I would hazard a guess, is precisely what she had in mind.

As for the Preston women, indecision reigns here as well. Motionless while dangerous insects creep into their hair (Hold Still), sanguine and naked in the face of traveling monks, (Just Drops, Really), even with a spike coming out of the head (We’ll Never Do That Again) they persevere with lacerating visual humor co-joined with word play used subversively in the title, or directly written onto the canvas. Whatever the animal is in One Button Off, it is surely female, and dressed for tea and sherry with Dottie at the Algonquin. With Comb Your Hair Jezebel the absent Jezebel, represented by two suspended combs, tines facing inward, answers the exhortation (by her mother?) not with words, but with a solid wall of black that vibrates affirmation in the negative. Black is often used as a conduit for Preston’s question and answer games. Take the portrait of the woman who dominates We’ll Never Do That Again, who for all the nostalgia implied by the use of the silhouette is not only disconnected from her body, but has that alarming bolt driven straight into her elegantly coiffed head. Which of the two calamities that has befallen her will “We” not do again?

As for the Preston women, indecision reigns here as well. Motionless while dangerous insects creep into their hair (Hold Still), sanguine and naked in the face of traveling monks, (Just Drops, Really), even with a spike coming out of the head (We’ll Never Do That Again) they persevere with lacerating visual humor co-joined with word play used subversively in the title, or directly written onto the canvas. Whatever the animal is in One Button Off, it is surely female, and dressed for tea and sherry with Dottie at the Algonquin. With Comb Your Hair Jezebel the absent Jezebel, represented by two suspended combs, tines facing inward, answers the exhortation (by her mother?) not with words, but with a solid wall of black that vibrates affirmation in the negative. Black is often used as a conduit for Preston’s question and answer games. Take the portrait of the woman who dominates We’ll Never Do That Again, who for all the nostalgia implied by the use of the silhouette is not only disconnected from her body, but has that alarming bolt driven straight into her elegantly coiffed head. Which of the two calamities that has befallen her will “We” not do again?

Yet for all the unsettling questions that go unanswered in these paintings, they are not sad pictures, not by a long shot. With an irreverent and politically charged sense of the absurd the artist creates a strange band of characters and anthropomorphic animals that challenge our perceptions of what it really means to be alive, to be hungry. They also give us the chance to reflect on a universal truth: no sooner do we gain command of life than circumstances beyond our control will no doubt shake the ground we stand on.

This shifting sense of reality is made manifest visually with Preston’s collage technique which relies heavily on the use of distressed recycled paper. The brown paper ~ a supermarket variety which we all know so well from a lifetime of carting groceries home ~ is put through a time consuming process in which she buries, drowns, irons, and over paints it with watery gauche, the better to see through. This alchemy transforms the uniform brown into a gorgeous tonal pallet that brings to mind sun-baked earth, cracked leather, butterscotch, wheat, parchment, and sand. Under her hand, ordinary paper becomes all but unrecognizable, yet somehow retains the very essence of itself.

As wonderful as her use of paper is, it is but half a visual pas de deux that takes an archaic reference of reflective gold, once used for its resplendence and to confer both spiritual and political power, and turns it on its head. Here, beneath a cracked pavement of cut and torn paper, a silvery world beckons. The inference, that there is nothing to stop us finding magic in the most prosaic of materials (in this case chewing gum wrappers) goes well beyond the trope that all that glitters is not gold. Viewed straight on, the juxtaposition of textural organic earth tones edged with silver registers as a flat opaque surface, but the moment the viewer commits ~ an eye moving across the canvas, a shift of the body ~ light catches along the irregularly cut edges of paper igniting a grid of luminous intersecting lines, electrifying the entire canvas.

As wonderful as her use of paper is, it is but half a visual pas de deux that takes an archaic reference of reflective gold, once used for its resplendence and to confer both spiritual and political power, and turns it on its head. Here, beneath a cracked pavement of cut and torn paper, a silvery world beckons. The inference, that there is nothing to stop us finding magic in the most prosaic of materials (in this case chewing gum wrappers) goes well beyond the trope that all that glitters is not gold. Viewed straight on, the juxtaposition of textural organic earth tones edged with silver registers as a flat opaque surface, but the moment the viewer commits ~ an eye moving across the canvas, a shift of the body ~ light catches along the irregularly cut edges of paper igniting a grid of luminous intersecting lines, electrifying the entire canvas.

Though they have the power to haunt you for days, these are not, to my mind, personal pictures. The artist herself remains very much a mystery to the viewer. The one exception is Goodbye Pina, painted after the death of the great dance choreographer Pina Bausch. With an initial nod to Giotto’s God in the heavenly direction Pina’s body takes in her contorted dance of death, Preston then refuses to relinquish her beloved muse to an idealized heaven. Pina dances into eternity only after she has risen through an undulating landscape and crossed over into a searing black monolithic sky. Relieved of her pain and made whole again, the power of this simply drawn figure in danceflight is remarkable.

A versifier of the highest order (she could easily have been a poet) words are used to great effect throughout the pieces in One Button Off. We Killed The Wrong Twin begs two questions: our complicity, and why the wrong twin needed to be killed in the first place; Bring It Back may be a refrain from the kid issuing the baby bottles from his mouth, or again, from the artist to the viewer about our inability to feed ourselves in what Preston, in her other life as a organic farmer, knows full well are dire times. The elongated goat in I Never Told You I Was A Contortionist, clearly is, while the caped baby in On Top Of The Mountain, clearly is not. Are these titles lies, or, by being put on notice to suspect all words, are we simply being cajoled into making new meanings from them? Take your pick. By consistently sneaking up on the viewer and whispering discreet possibilities in our ear, on both an intellectual and a sensual level Susan Preston has made it clear in this collection that we are free to consider all options. Art that exhibits this level of profundity seeks not only to claim the epicenter of our attention, but creates its own morally complex force field. To the man in the train station I would say “Simple faces, complicated lives.” Much like our own.

(Originally posted November 17, 2010)

All of Healdsburg turned out for the opening night of Susan Preston's one woman show ~ One Button Off~ last Friday evening. Thanks to an insane Barndiva cocktail called The Contortionist and a surfeit of always wonderful Preston wines, no one seemed to mind the wall to wall crowds. (We apologize to any of our guests who did not get to taste the spicy chopped Mediterranean salad we served on Lou's baguettes or our crispy tempura string beans.)

(originally posted June 2, 2010) Studio Barndiva

Studio Barndiva is proud to announce the opening reception for Photographer Wil Edwards’ Art Of The Rind series, on Sunday, June 13, between the hours of 3:00 – 5:30.

The reception for Edwards’ astonishing new exhibit of limited edition color pigment prints is the first showing in our new gallery space. We are thrilled it will be co-hosted by some of America’s premier artisan purveyors.

Join Studio Barndiva and Cowgirl Creamery, Laura Chenel, Pt Reyes Cheese Company, The Fatted Calf, Cheese Plus & the vintners of Kelley & Young Wines for a stimulating and delicious afternoon celebrating the art of cheese, as never captured before.