Just as the term ‘farm to table’ should imply a direct connection to an actual place where things are grown, ‘nose to tail’ carries with it a literal meaning: start with a whole animal and render as many parts of it delicious as talent and time allow.

There are great reasons to cook and eat this way. Starting with the extremities and moving through a properly raised animal you have brain, heart, liver, tongue, kidneys, sweedbreads, caul fat ~ all nutritious with incredible potential for tasting delicious. Our ancestors in the food chain saw using every part of the animals they killed as a way to honor the exchange of life for sustenance and warmth. They were also hedging their bets, never sure where or when they'd find their next 'free range' protein rich meal.

Which, sadly, isn’t that far off from where we find ourselves today. Grazing land is a rapidly diminishing resource in the world, while the skills needed to raise and humanely dispatch healthy animals “the old fashioned way,” because of our tragic reliance on CAFO's, has become a lost way of life. For those of us who still have access to pasture raised animals, cooking nose to tail honors every step of the journey that goes from animal, to farmer, to chef, to eater. It encourages us, in the most wonderful way possible, to use as many parts of these precious animals as we can.

But nobody said it was pretty. In a society that gorges on all manner of evisceration day after day, night after night, on screens big and small, we are still, by and large, squeamish as a nation when looking into the animals we eat. Food blogs are inordinately obsessed with staging only the most beautiful pictures ~ which fun as they are to look at ~ tell an incomplete story. Whatever the disconnect (perhaps fascination with fictional gore allows a certain distance to real death) it's important to post images now and again that honestly document what it looks like to cook the way we do. We do not wish to offend. But for those of us still eating and loving animal proteins raised sustainably, getting as close as we can to the history, the science, and yes, the mystery of why we love eating them is part of the story of our lives.

Mimi and Peter Buckley get this. Their two much admired food production enterprises in Sonoma and Mendocino are deeply respectful of land, animals and people. Front Porch Farm, here in Healdsburg, produces organic fruits and vegetables and Mimi’s great love ~ flowers. Up Hwy 128 in the heart of Yorkville, where they have been renovating the old Johnson spread, Peter and a talented young crew are raising heirloom Cinta pigs.Cintas are classic salumi pigs, usually weighing in at well over 300 lbs at slaughter. But when Ryan heard about Acorn Ranch he began to dream much smaller, about the size of the milk fed pigs he loved to cook at The French Laundry. He wondered aloud if the Buckleys were open to producing something special for us. They were. And so we received two 30 lb pigs a few weeks ago, beautiful animals he set about cooking "through" before inviting Peter, Mimi and their ranch and garden managers to dinner.

Several skill sets are needed for nose to tail cooking, but they all start with great butchery ~ the cleaner and closer the cut, the more protein per lb. Each part of an animal is then prepped and cooked using often laborious techniques where the main objective is teasing flavor out of each cut with an understanding of texture and how each cut will react to heat. It takes optimizing the characteristics of each region of the animal, understanding the way grain runs in sub-primal cuts, fat to muscle ratio, which bones to roast, which to braise. Nose to tail is not a proprietary culture but one about taking nourishing culinary traditions and playing them forward. The techniques Chef relies upon, ones he learned working alongside Richard Reddington and Thomas Keller, key off preparations handed down the centuries from country kitchens where the main objective was to marginalize waste. Chefs of this caliber, while pulling on those traditions, have taken nose to tail taken to a whole new level.

Tête a cochon is a good case in point. It is all about using up the least lovely, hard to get to bits in the head. As Drew broke down the whole animal and went about portioning it, Chef wrapped the head in cheesecloth and slowly braised it in a stock with leeks, apples, white wine, garlic & herbs. He then peeled everything off the bones, discarding the fat and gristle, mixing the soft bits of meat with the thinly sliced tongue and ears. This mixture was then seasoned and tightly wrapped in plastic wrap into a roulade, which he put into an ice bath to start the consolidation of protein and fats, then left to rest overnight in the walk-in. (Another route would have been to pack the softly rendered collection of head meats into a terrine mold and serve them cold.)

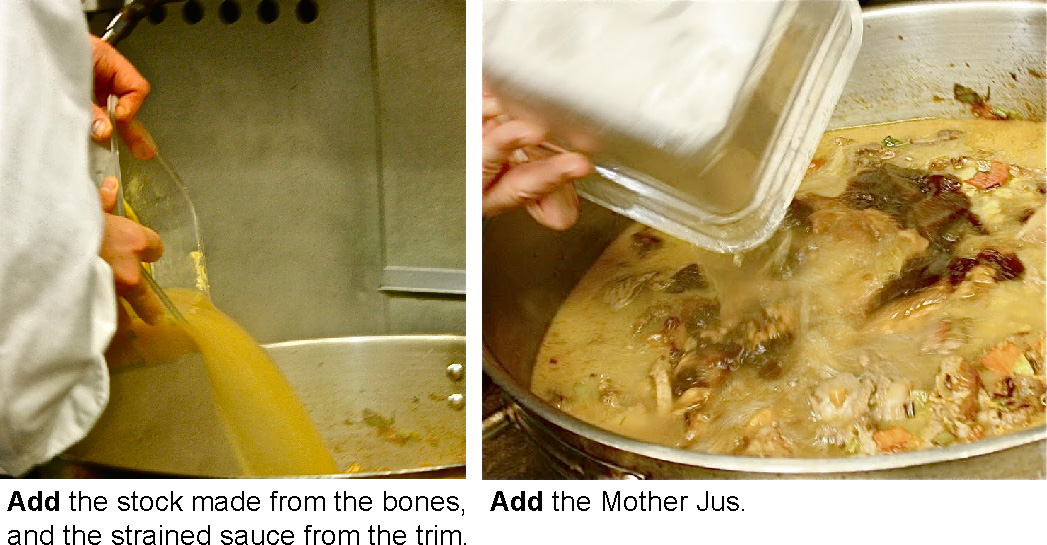

As the orders came in the roulade was cut into 1 1/2”discs, brushed with Dijon, dusted with Panko and spices, and sautéed in a bit of butter, garlic and thyme until crisp. Tête is often served with gribiche but Ryan finished this first course dish simply, with a sprinkling of chives and a crispy trail of sublime Acorn Ranch bacon. For a special entrée tasting he did the same night, (our first image, above) he served the chop, belly and shoulder, with a summer spin-off of bacon, blistered tomato and avocado, a brighty acidic, fresh olive tapenade on the side. The shoulder in this dish was one of the best I've ever had, bathed in an sauce he'd made by heating the bone jus with a touch of butter, letting it reduce slowly in the pan while basting to form a beautiful silky glaze.

There is no taking away the initial visceral intensity of watching a dish like this prepared from scratch. But beyond the fact that the tradition of nose to tail produces food which is incredibly nuanced and nutritious, we consider ourselves lucky, if not blessed, to be able to cook this way for you.

Follow Us in 2014!

All text Jil Hales. Photos © Jil Hales