(originally posted November 10, 2010)

Simple lines…complicated faces, the man next to me mumbled. He was talking to himself, but I followed his gaze to a poster across the underground track on the wall just beyond where we were standing, waiting for the train. London was awash in great art shows that winter but the Giotto Exhibit, which the poster was touting, was not high on my list. Religious painters are not my thing really. Yet once the stranger had drawn my attention to the image of the Madonna and child I found I could not look away. Beneath a film of soot the face of a woman who lived centuries before me glowed with incandescent dignity. I felt a better person just being in the same space with her.

Simple lines…complicated faces, the man next to me mumbled. He was talking to himself, but I followed his gaze to a poster across the underground track on the wall just beyond where we were standing, waiting for the train. London was awash in great art shows that winter but the Giotto Exhibit, which the poster was touting, was not high on my list. Religious painters are not my thing really. Yet once the stranger had drawn my attention to the image of the Madonna and child I found I could not look away. Beneath a film of soot the face of a woman who lived centuries before me glowed with incandescent dignity. I felt a better person just being in the same space with her.

I thought about that moment a few weeks back as Susan Preston and I moved through her studio on West Dry Creek looking through a collection of paintings that would comprise her one-woman show at Studio Barndiva, which opens November 10th. It may seem like a stretch to compare the work of a woman living today in a small farming community in Northern California with a man who, in wrestling with how to present the human form realistically on a flat surface, developed his own language for three-dimensional space that changed the course of art history. But that’s the thing about remarkable art: its capacity to capture the singular attributes which make us human transcend both time and providence.

Susan Preston is also an artist who begins with an extremely shallow picture plane that she fills, sparely, with ‘naïve’ characters who challenge our notion of what it means to be spiritually relevant. Whereas artists of Giotto’s time painted from a place infused with religious certainty, Preston, a woman very much of our time, poses a series of complex moral dilemmas. She does this through the development of a mixed-media/mixed-message language that is both literary and textural, resulting in work that, very much like the great Italian master, leaves us believing that the spiritual is ever present.

Take the half naked woman sheltering beneath the waves of Just Drops, Really. Is she the artist viewing history from a distance, or mother nature herself surreptitiously controlling the faceless monks as they make their Canterbury-like way down the mountain, catching rain drops any which way they can? She views the scene with a curious detachment from her self-contained envelope, neither strident nor embarrassed in her nakedness which, despite her age, radiates a rakish charm. Step away from the canvas and you are left contemplating an utterly contemporary question Giotto never had to consider: resources and who controls them. This confrontation without violence is a recurrent Preston theme, one that hints, if not confers, contemplative power.

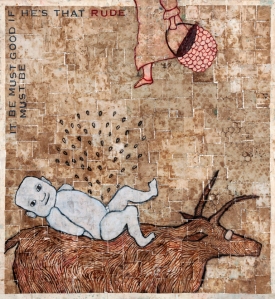

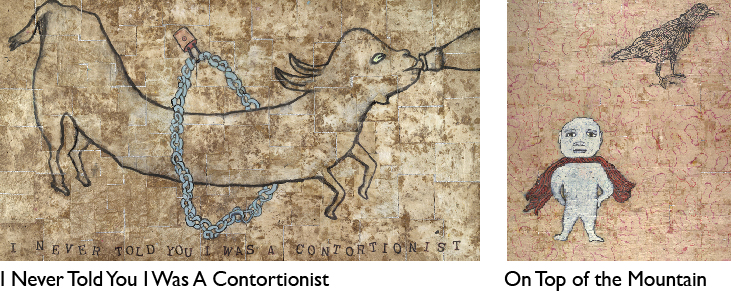

This is especially true of her babies. These old souls, wise as Buddhas, complacent as cool California dudes, resonate without having to interact with the spare natural order that surrounds them. The caped baby in On Top of the Mountain and little boy on the back of a yak in Upward Tears are all but oblivious to the crow and farm woman who respectively share their world, yet the artist manages to convey that a powerful connection exists between them. The babies of Heaven of the Milk Tree pay little or no attention to the forbidding tree that dominates their landscape, yet their direct but unreadable expressions challenge the viewer to wonder if those dripping fruits which loom above them are filled with milk, or poison (life-giving or deadly). I Can’t Decide, the artist avers, in the title of Milk Tree’s companion piece, leaving us forced to engage with the work on yet a deeper level if we want to arrive at an answer. Which, I would hazard a guess, is precisely what she had in mind.

As for the Preston women, indecision reigns here as well. Motionless while dangerous insects creep into their hair (Hold Still), sanguine and naked in the face of traveling monks, (Just Drops, Really), even with a spike coming out of the head (We’ll Never Do That Again) they persevere with lacerating visual humor co-joined with word play used subversively in the title, or directly written onto the canvas. Whatever the animal is in One Button Off, it is surely female, and dressed for tea and sherry with Dottie at the Algonquin. With Comb Your Hair Jezebel the absent Jezebel, represented by two suspended combs, tines facing inward, answers the exhortation (by her mother?) not with words, but with a solid wall of black that vibrates affirmation in the negative. Black is often used as a conduit for Preston’s question and answer games. Take the portrait of the woman who dominates We’ll Never Do That Again, who for all the nostalgia implied by the use of the silhouette is not only disconnected from her body, but has that alarming bolt driven straight into her elegantly coiffed head. Which of the two calamities that has befallen her will “We” not do again?

As for the Preston women, indecision reigns here as well. Motionless while dangerous insects creep into their hair (Hold Still), sanguine and naked in the face of traveling monks, (Just Drops, Really), even with a spike coming out of the head (We’ll Never Do That Again) they persevere with lacerating visual humor co-joined with word play used subversively in the title, or directly written onto the canvas. Whatever the animal is in One Button Off, it is surely female, and dressed for tea and sherry with Dottie at the Algonquin. With Comb Your Hair Jezebel the absent Jezebel, represented by two suspended combs, tines facing inward, answers the exhortation (by her mother?) not with words, but with a solid wall of black that vibrates affirmation in the negative. Black is often used as a conduit for Preston’s question and answer games. Take the portrait of the woman who dominates We’ll Never Do That Again, who for all the nostalgia implied by the use of the silhouette is not only disconnected from her body, but has that alarming bolt driven straight into her elegantly coiffed head. Which of the two calamities that has befallen her will “We” not do again?

Yet for all the unsettling questions that go unanswered in these paintings, they are not sad pictures, not by a long shot. With an irreverent and politically charged sense of the absurd the artist creates a strange band of characters and anthropomorphic animals that challenge our perceptions of what it really means to be alive, to be hungry. They also give us the chance to reflect on a universal truth: no sooner do we gain command of life than circumstances beyond our control will no doubt shake the ground we stand on.

This shifting sense of reality is made manifest visually with Preston’s collage technique which relies heavily on the use of distressed recycled paper. The brown paper ~ a supermarket variety which we all know so well from a lifetime of carting groceries home ~ is put through a time consuming process in which she buries, drowns, irons, and over paints it with watery gauche, the better to see through. This alchemy transforms the uniform brown into a gorgeous tonal pallet that brings to mind sun-baked earth, cracked leather, butterscotch, wheat, parchment, and sand. Under her hand, ordinary paper becomes all but unrecognizable, yet somehow retains the very essence of itself.

As wonderful as her use of paper is, it is but half a visual pas de deux that takes an archaic reference of reflective gold, once used for its resplendence and to confer both spiritual and political power, and turns it on its head. Here, beneath a cracked pavement of cut and torn paper, a silvery world beckons. The inference, that there is nothing to stop us finding magic in the most prosaic of materials (in this case chewing gum wrappers) goes well beyond the trope that all that glitters is not gold. Viewed straight on, the juxtaposition of textural organic earth tones edged with silver registers as a flat opaque surface, but the moment the viewer commits ~ an eye moving across the canvas, a shift of the body ~ light catches along the irregularly cut edges of paper igniting a grid of luminous intersecting lines, electrifying the entire canvas.

As wonderful as her use of paper is, it is but half a visual pas de deux that takes an archaic reference of reflective gold, once used for its resplendence and to confer both spiritual and political power, and turns it on its head. Here, beneath a cracked pavement of cut and torn paper, a silvery world beckons. The inference, that there is nothing to stop us finding magic in the most prosaic of materials (in this case chewing gum wrappers) goes well beyond the trope that all that glitters is not gold. Viewed straight on, the juxtaposition of textural organic earth tones edged with silver registers as a flat opaque surface, but the moment the viewer commits ~ an eye moving across the canvas, a shift of the body ~ light catches along the irregularly cut edges of paper igniting a grid of luminous intersecting lines, electrifying the entire canvas.

Though they have the power to haunt you for days, these are not, to my mind, personal pictures. The artist herself remains very much a mystery to the viewer. The one exception is Goodbye Pina, painted after the death of the great dance choreographer Pina Bausch. With an initial nod to Giotto’s God in the heavenly direction Pina’s body takes in her contorted dance of death, Preston then refuses to relinquish her beloved muse to an idealized heaven. Pina dances into eternity only after she has risen through an undulating landscape and crossed over into a searing black monolithic sky. Relieved of her pain and made whole again, the power of this simply drawn figure in danceflight is remarkable.

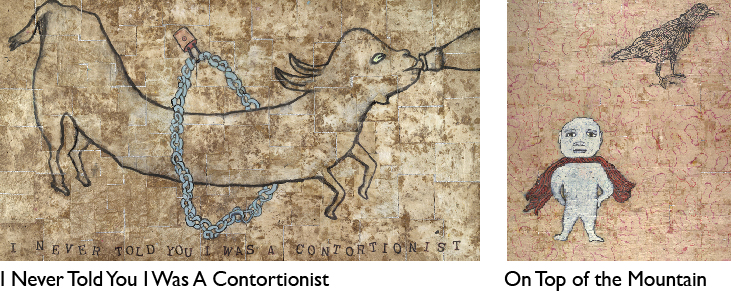

A versifier of the highest order (she could easily have been a poet) words are used to great effect throughout the pieces in One Button Off. We Killed The Wrong Twin begs two questions: our complicity, and why the wrong twin needed to be killed in the first place; Bring It Back may be a refrain from the kid issuing the baby bottles from his mouth, or again, from the artist to the viewer about our inability to feed ourselves in what Preston, in her other life as a organic farmer, knows full well are dire times. The elongated goat in I Never Told You I Was A Contortionist, clearly is, while the caped baby in On Top Of The Mountain, clearly is not. Are these titles lies, or, by being put on notice to suspect all words, are we simply being cajoled into making new meanings from them? Take your pick. By consistently sneaking up on the viewer and whispering discreet possibilities in our ear, on both an intellectual and a sensual level Susan Preston has made it clear in this collection that we are free to consider all options. Art that exhibits this level of profundity seeks not only to claim the epicenter of our attention, but creates its own morally complex force field. To the man in the train station I would say “Simple faces, complicated lives.” Much like our own.

Bastidor Santos mannequins were traditionally paraded around the streets in Spain during religious holidays, adorned with elaborate costumes.

Hand carved Narwood, these are based on an original Spanish Colonial design:

Bust $290

Mannequin $300

Bastidor Santos mannequins were traditionally paraded around the streets in Spain during religious holidays, adorned with elaborate costumes.

Hand carved Narwood, these are based on an original Spanish Colonial design:

Bust $290

Mannequin $300 Just in:

Manok Cohen

The Cloud

40 x 48

$2900

Just in:

Manok Cohen

The Cloud

40 x 48

$2900